19-07-2018

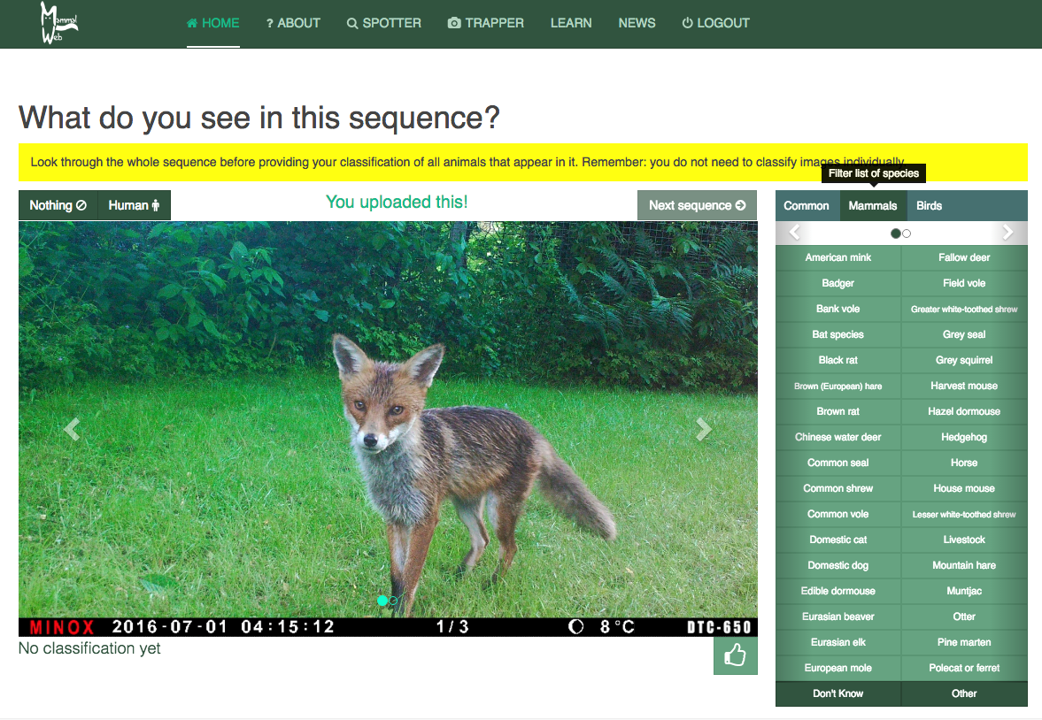

We (the project team, plus all of our participating volunteers) have published our first paper based on MammalWeb! The paper is in the journal Remote Sensing in Ecology and Conservation, and can be found here. When we think of Remote Sensing, we often think of satellite observations (a source of data that can be remarkably handy for ecologists, as well as many land managers, plus other scientists and social scientists). However, Remote Sensing can cover many types of data collection for which the presence of people is not necessary at the time of data acquisition. Camera trapping is, thus, a good example of a remote sensing approach.

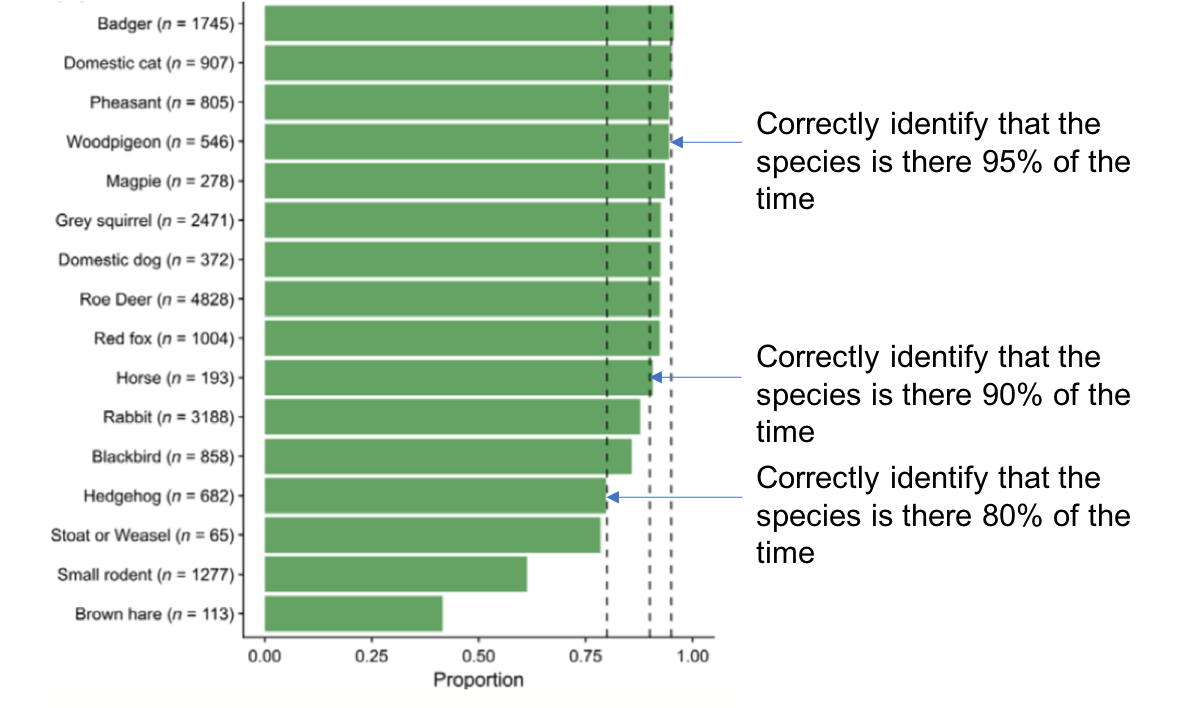

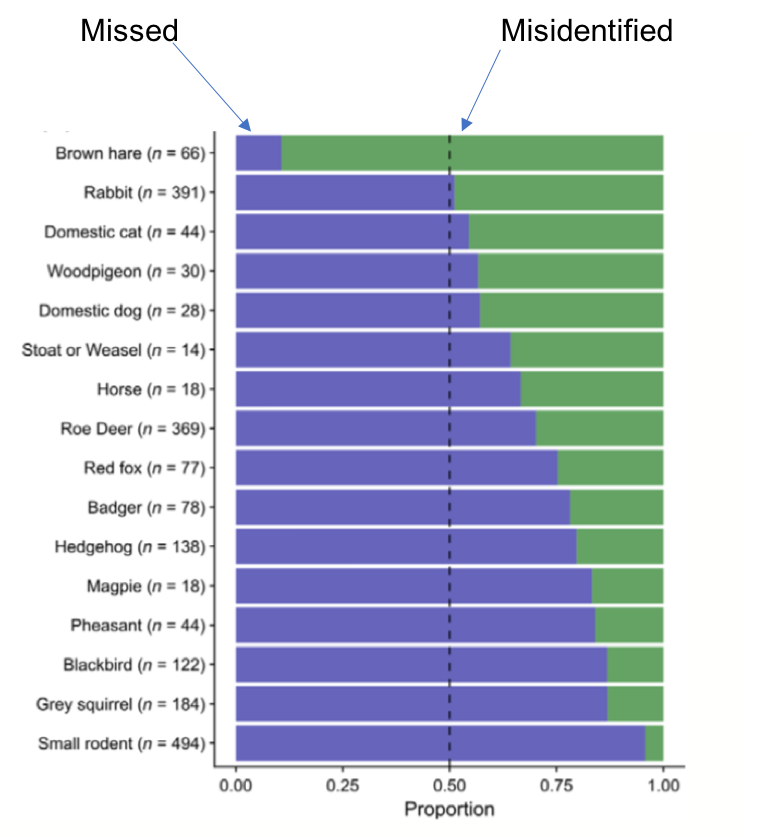

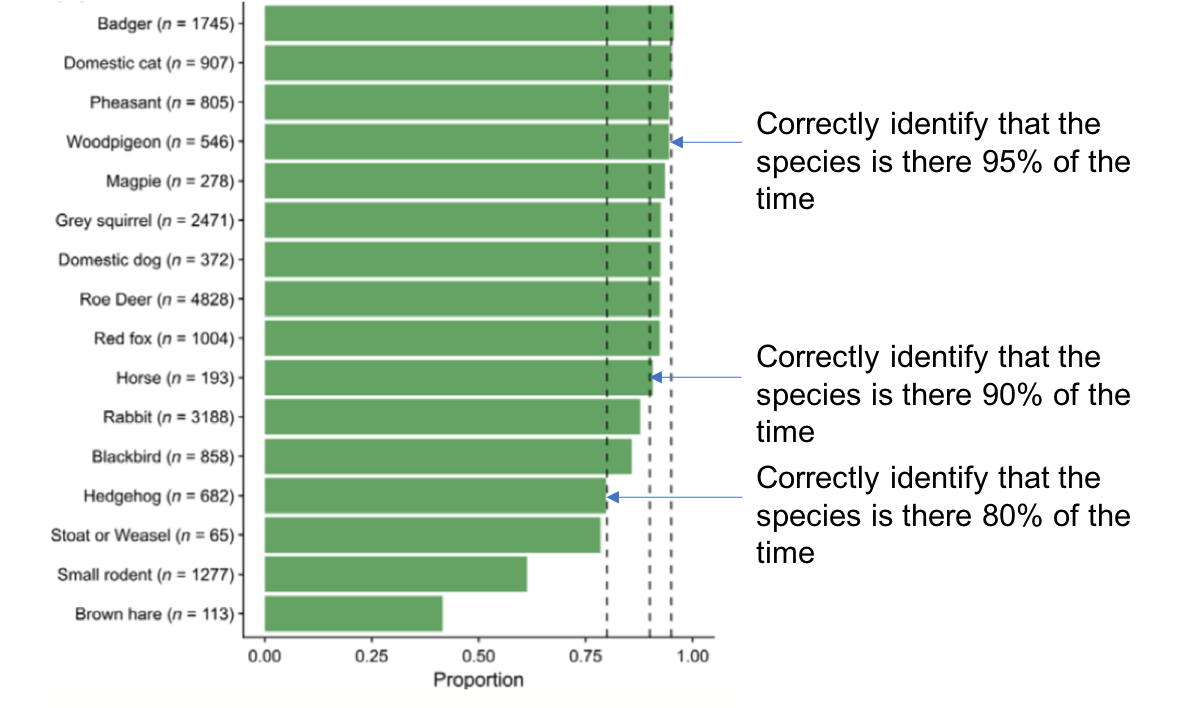

A pre-requisite for making use of the data collected by all of MammalWeb's participants is knowing what's in the images. By comparing user-submitted classifications to a set of over 10,000 image sequences that have been looked at by "experts" to determine their subjects, we can learn about how confident we can be about those classifications. Happily, it turns out that participants are very good at identifying what's in an image sequence. We need lots of examples to get a good idea of how accurate participants usually are, so we focused on 16 of the most commonly-occurring species (or species designations). When those species occurred in a sequence, we looked at all the submitted classifications and asked how many of them correctly said that the species was pictured. For almost all of the commonly-occurring species, that figure was 80% or more. For several species, it was closer to 95%! Given the risk, with all trail cameras, of getting blurry, dark, partial, or otherwise indistinct images, we think this is a real testament to the skill and dedication of those using the website!

Fig. 1. In general, spotters show high levels of accuracy.

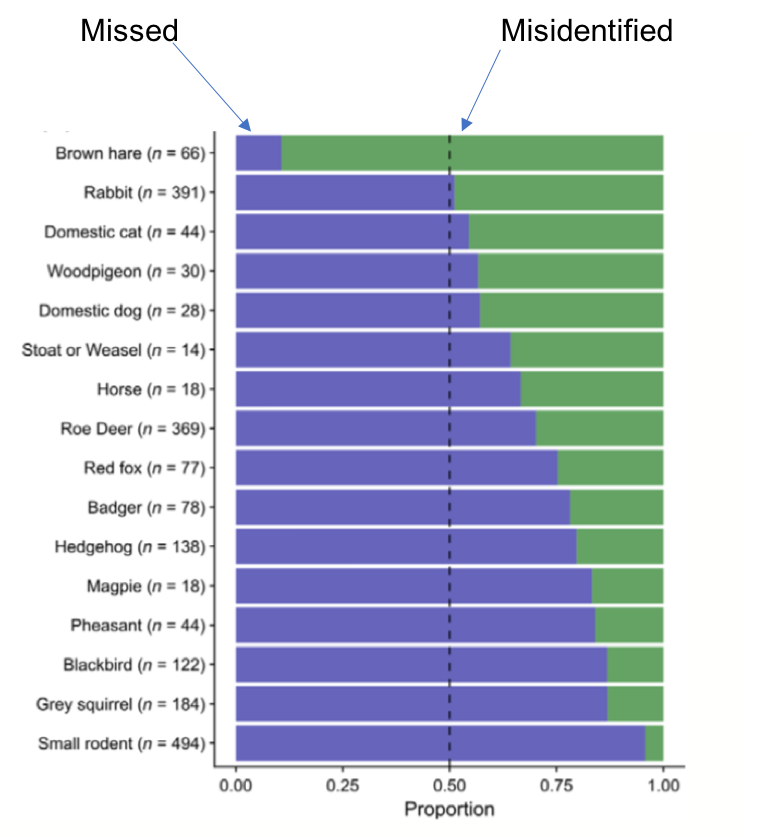

Two "species" for which accuracy is notably lower are small rodents and brown hares. Further analyses looking at the inaccurate classifications in those cases show that they arise for different reasons. In particular, small rodents are often overlooked altogether, because they are often visible only from their eye-shine. We hope that our site developments (especially the new approach to being able to move backwards and forwards through a sequence, which can help to identify any sort of movement) will reduce this problem. By contrast, brown hares show lower accuracy than most other species because they are often misidentified as rabbits. This is understandable, given their many similarities. However, we would encourage anyone who is uncertain to take a look at web tutorials, such as this page or this one.

Fig. 2. Reasons for incorrect classifications by species or species group. Where blue predominates, the species is more often missed than misclassified; green indicates the proportion of errors that arise from misclassification.

Clearly, based on these numbers alone, we can be much more confident of classifications regarding some species than others. This might mean that we could remove many image sequences, allowing users to focus on the less distinct, the more unusual, or those that prove harder to reach consensus about. However, that might result in a far less rewarding time for Spotters. At present, we are keeping a close eye on techniques for automatic image analysis. These might, at the very least, allow us to remove sequences very likely to contain no wildlife, which - based on comments received - would probably be very popular with many of our contributors!

English (United Kingdom)

English (United Kingdom)  Czech (Čeština)

Czech (Čeština)  Nederlands (nl-NL)

Nederlands (nl-NL)  Magyar

Magyar  Deutsch (Deutschland)

Deutsch (Deutschland)  Croatian (Hrvatski)

Croatian (Hrvatski)  Polski (PL)

Polski (PL)  Español (España)

Español (España)