16-06-2020 by Roland Ascroft

Many bird and mammal species may be classified as sexually dimorphic (i.e., males and females differ visibly in their appearance) like pheasants or deer, or monomorphic (i.e., the two sexes look alike) like dunnocks or hares. Obviously, terrestrial mammals in Europe are not truly monomorphic because of their external genitalia, but these are only sometimes visible on trail camera images. Secondary sexual characteristics such as antlers in deer or tusks in wild boar make it much easier to separate the sexes for much of the year, but many mammals are sexually dimorphic by size, and this also occurs in birds (particularly some birds of prey). So, for mammals and birds in the UK (merely because this is where we have sufficient data), how often do spotters separate the sexes?

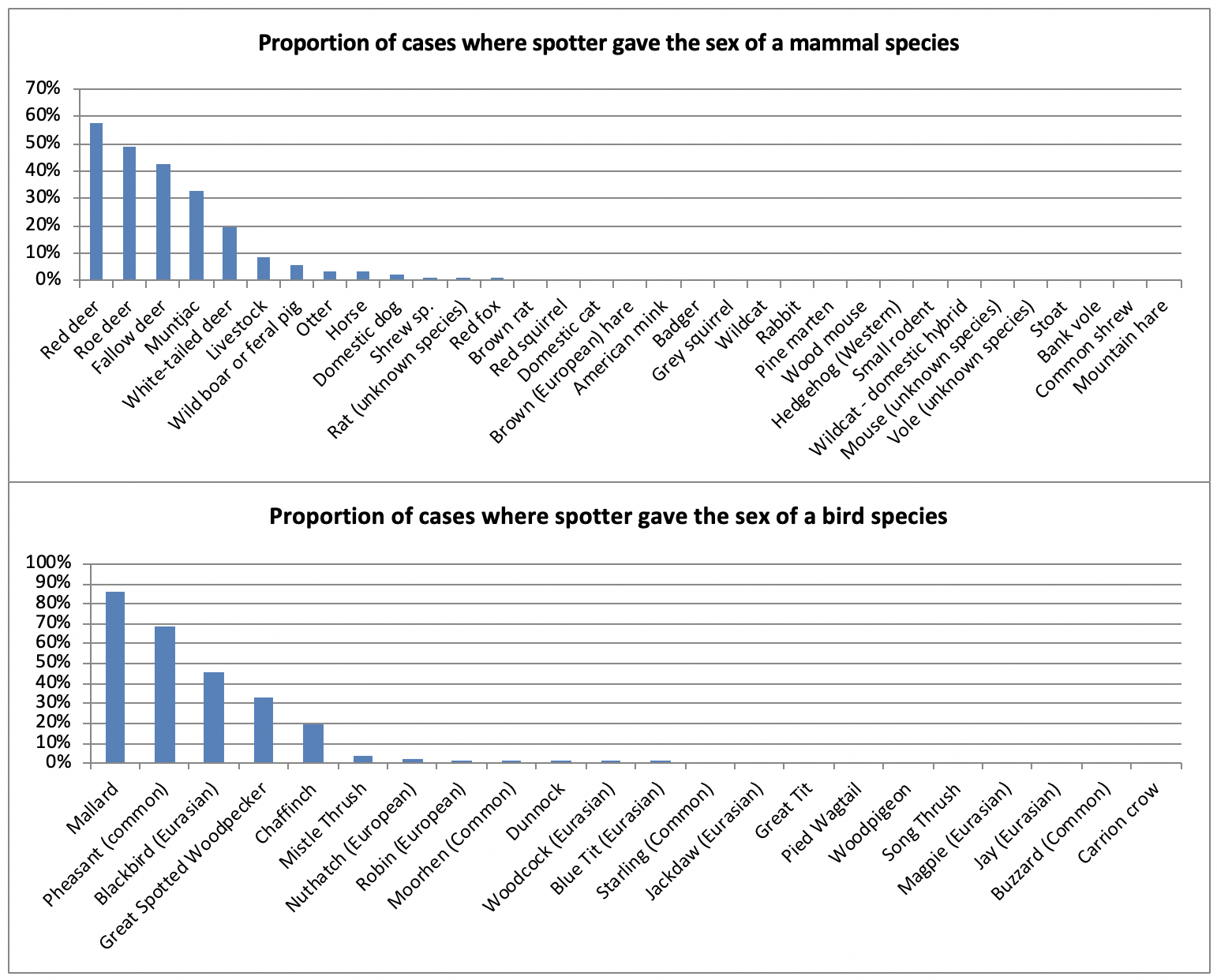

Percentage of identifications where the spotter gave the sex (for species with more than 100 classifications)

Not surprisingly, deer rank top in terms of sex-separation in mammals, and the top 5 bird species are also ones which are obviously dimorphic, in this case in their plumage. One might expect Pied Wagtail to be included there, but it comes in at number 16, below several sexually monomorphic species. For most species, most of the time, spotters cannot or do not attempt to identify the sex of a bird or mammal.

One of our most dimorphic mammals in terms of size is the stoat with males being much larger than females, and yet there were zero attempts to give its sex. This may be because of the difficulty of estimating size on a picture when only one individual is present. In case you think size does not matter when it comes to sex, most of these species breed seasonally, and the size of their testes changes with season, driven by a hormonal cycle. This has been measured in roe deer, for example (Short R.V. & Mann T. 1966. The sexual cycle of a seasonally breeding mammal, The Roebuck (Capreolus capreolus) J. Reprod. Fert. 12,337-351).

English (United Kingdom)

English (United Kingdom)  Nederlands (nl-NL)

Nederlands (nl-NL)  Magyar

Magyar  Deutsch (Deutschland)

Deutsch (Deutschland)  Croatian (Hrvatski)

Croatian (Hrvatski)  Polski (PL)

Polski (PL)  Español (España)

Español (España)